The story of Boxes

Along the Dab sitting across on a warm and comforting silk carpet, an old man and his wife gaze into the twilight overlooking the street… savoring a smoke from a hookah… pipe in one hand, the other resting on the lap. Through the wide-open windows, their silhouettes look identical, both enveloped within their beige-grey Fehrans, with a highlight of white overturned sleeves. The golden flicker held gently on the wick of the oil lamps lights up the evening. They are absorbed in their own little world, enjoying the cold breeze caressing their red cheeks…

kashmir papier-mâché

There is, however, a clear difference in the assortment of things besides them. The man with a white turban on his head has a wooden study desk next to him… with a stack of paper, inkpot and pen readily waiting for him to snap out of his thoughts to pen something down. And he does… looking at the colorful birds painted on the pen case, while he lifts the pen up. He writes…

“We have only learnt to make boxes around everything we were given… literally and figuratively, in 2D and in 3D… some go ahead and make those boxes look so beautifully essential that we can’t help but incorporate them in our lives, while there are always a few forced ones around only waiting to be replaced. The beautiful ones however, like this Kalamdani are a delight to have. It holds in it a powerful weapon of the worlds of imagination that are waiting to be unboxed. This Kalam, however, needs to be held in the right hands to be able to say of those worlds honestly. Like the story of this kalamdani, that goes back to the times when Kashmir became the first and the only paper-producing region in this subcontinent.

The first paper industry developed in Kashmir was established by Sultan Zain-ul-Abedin in 1417-67 AD after he returned from detention in Samarkand. He brought along artisans of various skills to develop crafts and introduce new trades in India. And soon, because of its quality, the Kashmiri paper or Khosur kagaz was much in demand in the world and the rest of the country for writing manuscripts. This brings to the mystery of why the art of painted papier-mâché in Kashmir was originally confined to making Kalamdan or the pen-case only and got to be known as Kari-Kalamdani. Due to the rapid growth of paper industry during this time, the demand for pens along with bookbinding and craft of making decorative book jackets in papier-mâché also flourished.

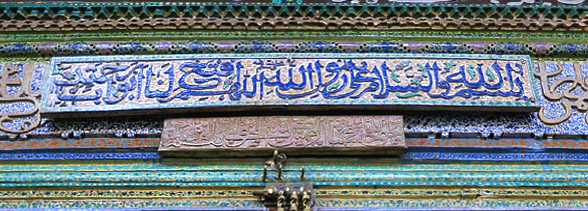

Calligraphy from Persia too took off as an artistic expression. Many calligraphers migrated from Persia and Central Asia to Kashmir during Zain-il-Abedin’s rule. The most renowned among them was Mohammad Husyn. When Mughal Emperor Akbar occupied Kashmir, Huysn received the title of Zarrin Qalam (the golden pen) from him. Later, the French used the word Papier-mâché painting work to refer to the boxes specially made to present Pashmina shawls that were imported from Kashmir; and these boxes were most sought after and were also sold separately at a premium in France. Hence, the craft of Kari-kalamdani was popularly known as papier-mâché painting in Europe.

Like a Cornucopia, Kashmir witnessed many diverse expressions of craft from poetry to music to space, to architecture, to weaving, to embroidery, to papier-mâché… These connections are evident in the motifs, colors and elements of its spaces and forms across crafts. Naqsh or Naqqashi is the foundation of any craft. It is the basic element, which adorns itself in various forms and mediums. Kari-kalamdani tradition had its individual masters or Naqqahgar, who sometimes signed their artworks.

During Mughal times, paper was used widely both for manuscripts and as a basis for tempera painting. The Mughals commissioned a large number of works made in Kari-kalamdani technique to make gifting products. The painting style was used on palanquins, howdahs and also to decorate the walls and ceilings of rooms. A smooth surface was created on the wooden base of the ceilings or walls with paper pulp and layered with polished Koshur kagaz to create a fine surface for the painting. This form of naqqashi was also known as kari-munaqqash (Munaqqash: decorated or picturesque). In the process of making a papier-mâché product, there are two distinct groups of artisans involved to produce the final article. The first is Sakhtasaz, who makes the object with paper pulp; the second is Naqqash, who does the ornamentation of the surface with colors.

The Sakhta-saz prepares the paper pulp pounding waste paper, cloth and other ingredients. The pulp is then shaped or given the form of the article with the help of Moulds. Traditionally clay moulds where used. Today the use of POP, wooden or metal moulds is prevalent. After the pulp has dried, it is removed from the mould. Depending on the complexity of the form of mould the dried pulp form is cut with a fine saw and glued back together and finished before the painting.

From here onwards the process is taken over by the Naqqahgar or Naqqashi and the ornamentation begins with the application of white solution consisting of gypsum and glue. After drying, the surface is polished with a wet stone until perfectly smooth. The subjects that get painted are Red and green apples, pomegranate, peaches, cherries, apricots or green almonds or walnuts, lotus and lotus pods, things of beauty, fish, birds, creepers, roses, Mughal patterns, deers, rabbits and the rest of the life forms, no human figures though.

Traditionally the color for the painting was made from natural pigments and minerals and it was a strenuous process to prepare them. The ground or zameen (the base coat) was commonly metallic, of gold, silver or of tin. Fine particles of ground tin, silver or gold were mixed with glue and applied on the surface and allowed to dry and then burnished with an agate. A light rub of amber varnish followed this and whilst wet, fine verdigris powder was spread to get a greenish-blue tone. Tin or gold foil imparted a subtle luster. For a red effect on luster a preparation of lac was used.

Color pigments were also imported from various places but Kashmir itself yielded black- from the walnut, as well as some other common colors and essentials-such as linseed oil, which mixed with gum resin formed the varnish. White lead came from Russia and verdigris was obtained from Surat or Britain. Lapis Lazuli for ultra-marine was bought from Yarkand. The painting on the pattern was done with a brush made from the hair of a Pashmina goat and pencils from those of cat fur (as described by Willam Moorcraft in his travelogues circa 1800 AD).

The practice of using natural pigments has languished over a period of time due to rampant commercialization of Papier-mâché products. A widespread use of synthetic colors and varnish is prevalent now.

The designs used in papier-mâché Naqqashi are very fine and need a great deal of skill and accuracy to achieve. The paintings are of two kinds, raised and flat. The raised type comes close to relief work. Birds and butterflies are sometimes represented in relief manner amongst flowers and foliage on a flat surface. The patterns are drawn free hand by the master Naqqashi and assistants do the job at various stages of filling color. And finally the master Naqqashi draws the outline to complete the painting, which is then coated with varnish.

The technique of painting on papier-mâché was also applied on woodcarving, especially windows, Khatambandh ceilings and furniture. Specimens of objects made of Papier-mâché of a date earlier than that of nineteenth century are very rare; mostly due to their fragile or perishable nature. But the fact that there was continuity in tradition from the fifteenth century onwards is clearly indicated by literary sources documented by William Moorcroft and a French traveler; Bernier’s travelogues from 1665. Some rare and fine specimens of these articles are preserved at the Victoria & Albert museum in London.”

As he was writing on his Koshur kagaz, he realized that it too was made from the same pulp as the kalamdani. Each sheet polished with a smooth shell or stone for a crisp glossy finish… his eyes started gleaming with blue light.

The woman, from the other side, also with a white cap on her head… fine mulmul drape covering her back from underneath it, responded with a similar shine and warmth in her eyes. The room was resonating with their love. Not so fond of boxes, she had many loosely tied Potlis behind her… the kids of the household often flocking around would run into her lap and she would carry them in her warm embrace, put her hand in one of the sacks and take out goodies. What all was inside them was a surprise to everyone… but no one ever left without a smile. Among her cherished offerings of love were fruits- a big red apple, pomegranate, peaches, cherries, a hand full of dried fruits like apricots from Ladakh or green almonds or walnuts, sundried tomatoes, baked grams, seeds of lotus pods… The apparently small sacks were also seen to give out things once in a while… things of beauty… like she once took out a copper Surmadani shaped like a fish for a girl she thought had fish shaped eyes, walnut wood and Kari-kalamdani cases, beautiful brass hand mirrors with roses etched on the glass, wicker and woolen toys, fresh pink roses… no one knew where they came from. The only time she would be out of the Dab was early in the morning, around 3 or 4 am and everyone knew she was going for her daily prayers and would be back in a few hours. Everyone loved to flock around them… rounds of storytelling and singing together over piping Kahwa and crumpling Bhakarkhanis would play day and night…..

Read more About kashmir papier-mâché ~ Gaatha.org

Gud india

Nice info we are also dealing in Kashmiri products. Now on your door step book online Kashmiri collection’s for more info visit http://www.gudindia.com