The Story & the storyteller!

In the Ramayana of Valmiki, there is an episode in which Hanuman has to increase himself in size and leap over an ocean. To perform the task at hand, Hanuman attains his full strength and as he waves his tail with joy, he expands himself in size, as large as the universe. As he leaps over one hundred yojanas and stands on top of Mount Trikuta, he gazes in wonder at the well-guarded city of Lanka, where Sita had been abducted by the demon-king Ravana. As Hanuman looks at all the demons and cruel creatures guarding the kingdom of Ravana, he becomes afraid that he would be spotted due to his huge size. Therefore, in an attempt to outwit these rakshasas, he begins shrinking himself and minimizes himself into a form which was barely visible and thus, he becomes a tiny creature, impossible to be spotted by anyone.

Through the medium of literature, the author can paint a vivid picture in the minds of his readers and grant them the possibility to imagine miraculous scenes such as the mighty Hanuman expanding and shrinking in size. But how does one bring such an imagery to life when these tales need to be reenacted, in a theatrical setting? It is at these moments when puppets come to the rescue!

In the shadow puppet theaters of Andhra Pradesh, as light projects on a large transparent screen, characters from the Ramayana and Mahabharata come to life in the form of puppets. These shows are able to bestow possibility to scenes which would be impossible to be performed in a naturalistic form. And thus, representations of the expansion and shrinking of Hanuman becomes possible through leather puppets which are of different sizes; there is the Vishwaroopa Hanuman puppet, over 6 feet and 7 inches in height, depicted as heroically defeating asuras and there is the Ashoka Vana Hanuman puppet who measures no more than 50 cm and is seen wandering the Lanka of Ravana, in his tiny form. (Read more about the making of these leather puppets here). Also, note worthy here is the Monkey-God form of Hanuman, implying his connection to both the worlds; earthly and godly. He also therefore is seen constantly shuttering between the two. Could, the shape shifting episode in the epic be a mere symbolic representation of this characteristic Hanuman possessed? To humbly downplay his stature while with earthly beings to not intimidate them and resume back to his grandeur while with Gods.

Through the medium of shadow puppetry, Tholu Bommalata (Tholu- leather, Bommalata- puppet dance ), the artists of Andhra Pradesh are able to bring to life the numerous mythological and folk tales of the subcontinent. The narration of these tales is able to give the audience an escape from the mundaneness of reality. But as important as the tales are, what becomes more crucial is how these tales are told and what are the diverse methods employed by the storyteller to make the experience vivid and vibrant for the listeners.

Skies filled with rains of arrows, large and fierce asuras causing chaos, shape-shifting monkeys who can fly, weapons which can take the form of humans, curses which can turn one to ashes and rivers flowing from the heavens, blessing the three worlds…these are just a few of the many captivating themes which feature in our mythological texts. And one of the most fascinating mediums used by many storytellers in India to fuse these themes with theater is by making inanimate objects animate and by giving these objects life through the will of a living spirit – this is the art of puppetry.

As old as civilisation, the tradition of narrating stories with the help of puppets has been a great source of entertainment and knowledge. Bringing down stories from generation to generation, the storyteller (sutradhara – holder of strings) acquires a vital role in puppet shows. In India, a diverse amount of puppet traditions thrive and to give life to this craft and artists from different regions of the subcontinent have mastered techniques to make unique puppets of many kinds. Today, we are going to be exploring some of these traditions, the stories they tell and the symbolism behind them.

Flourishing in parts of Karnataka are two popular string-puppet traditions; Sutrada Gombeyata’, where the word ‘sutra’ connotes string, and ‘Yakshagana Gombeyata’, the word ‘yakshagana’ connoting ‘the song of the celestial beings’. The term ‘gombeyata’ is meant to imply dancing. These puppets are usually made to perform in front of the temples of goddess Kali – thus, securing their art form as sacred. For these puppeteers, whose families have been devoted to this craft for generations, puppets play a very significant role in their economy and also religiously.

The renowned art-historian Vidya Dehejia has talked about how extolling the physical beauty of our gods and goddesses is one of the strands through which a devotee expresses his/her devotion (bhakti). Since ages, within the Hindu tradition, the beauty of the divine has been imagined in the form of fascinating sculptures. In a similar manner, with great dedication and reverence, craftsmen create their puppets and bestow certain qualities on them to distinguish them as gods. The colours on the faces and the facial characteristics of these puppets represent the types of roles that they are playing and thus, puppets representing the divine get distinguished by their refined features and beautiful faces…. often defining the very parameters of beauty for the society. Professionally too, the jobs of these puppeteers are considered divine since the stories which puppets narrate are from sacred texts and retelling these tales is in itself an edifying experience which bestows merit. Those who narrate these stories and those who listen to them are said to be freed of their sins, gain honour in their lives and also attain the heavenly realms. “One can see the importance of attaching such rewards to keep the stories that entirely depended upon oral traditions and folk lores to keep them alive. However, what gets percolated down the layers of generations is the essence of the epic often mingled with the local flavour.”

The yakshagana form of puppetry is based on the traditional dance-dramas held to celebrate agrarian deities – the makers give these puppets well-defined bodily structures, articulated hands, legs and feet and bestow huge headdresses, such as crowns with mirror work, on them. Set up against a huge black cloth and presented on a revered stage, as the puppet-masters hide behind a dark black screen and narrate tales musically, they give life to these puppets, playing various roles; some puppets are kings while some are mighty heroes; some of them are princesses while some of them are demons; some are mere mortals while some are immortal gods! As these puppets perform episodes from the Ramayana, Mahabharata, the Puranas and local folklore – these stringed inanimate creatures keep the audience at the edge of their seats as the plot of the story keeps unfolding.

There might be situations when a single storyteller would need to hold the strings and tell the tale of two characters possessing qualities which are poles apart. In such a case, it would not only be a prerequisite for the puppeteer to be well-versed with the story he is telling but he would also need to possess the ability to jump from one mind to another. If the storyteller needs to depict a battle-scene between an asura and a righteous king, it becomes his responsibility to do justice to both the characters by appropriately exploring the thinking of both the sides. Much like in real life, in our tales too, hardly does the ‘antagonist’ ever realize that he represents ‘unrighteousness’. This antagonist, who has a mind of his own, would consider himself and his actions to be on the path of ‘righteousness’. And thus, the storyteller needs to depict exactly this – he cannot let his ideas colour the story and thus, the puppeteer cannot afford to degrade the asura while glorifying the king. In this way, the story itself, at times, holds the string and controls the puppeteer. “Though he has already painted the puppet of the unanimously accepted antagonist with symbolisms engrained in social conscience as demonic; the fangs, the bulging eyes and the unrefined features…thereby making his stance on the entire episode very clear right at the beginning.”

Once the stage is set and the puppeteers are ready, these puppet-shows usually begin by chanting a prayer in respect of the elephant god Ganesha, who is present as a puppet himself on the stage, being shown reverence to, by the puppet of a dancing girl, who moves rhythmically while performing the fire offering. “One is compelled to think of the number of times we have come across a Goddess being shown reverence to by a dancing boy. Do our epics often underplay the role of women and especially the powerful women of their times, by either casting them as righteous wives (and nothing more), ganikas (prostitutes), or goddesses with their only highlighted attribute of greatness being their ability to give; unconditionally and unquestionably… while Gods went around gaining and loosing lands and loves, wives and kingdoms. The only exception to it being Kali, the fierce one and Shiva, who’s birth or end are unknown to us. These epics are a tale of the past, not exactly the facts, they have been known to be modified regionally to create a more local and believable narrative everywhere. And the societies that modified them have been among other things increasingly gender biased.”

As the play begins, one can imagine a captivated audience, being enthralled by the episodes from the epics being presented in front of them. There are reenactments of Hanuman burning the palace of Ravana with his tail, of the fights in Mahabharata with puppets holding swords, of demon-puppets with bulging eyes fighting a fierce battle with monkeys and of slaying of the ten-headed puppet of the demon-king Ravana by the alluringly sculpted puppet of Lord Rama – as the Drama unfolds in front of men, women and children, an ocean of emotions erupts within them. In gombeyata traditions, the pupeeteers are able to give actuality to unrealistic and magical acts. For example, actual fire is lit up on the tail of the puppet-Hanuman as he flies around to burn the lanka of Ravana!

As the show unfolds, the audience gets more and more engrossed. An episode in the Ramayana reveals to us how Rama gets to hear his own story when his two sons, Kusha and Luva, narrate the Ramayana for him. As the pair retell the story of their father, the audience who gets the opportunity to listen to this glorious tale, exclaim: “The things the story speaks of occurred a long time ago but it feels as though they are happening right before our eyes!” In a similar manner, when these puppet shows reenact these stories, they are able to establish a connection between the audience of today and the tales which belong to a time, much before ours. As the tale gets told, viewer become a part of the story and this is best exemplified by a quote of A.K. Ramanujan; “the listener can no longer bear to be a bystander but feels compelled to enter the world of the epic”.

The listener is also not a bystander because to an extent, he too has the power to influence the puppeteer and the story. The storyteller has the ability to maneuver the audience’s reaction and in this way, not only does he have the ability to hold the strings of his inanimate objects, but also his animate audience – by steering their reactions in a particular direction. However, opposing this force is that of the audience, for they play a crucial role in how the show is going to unfold. The way the audience reacts, affects the story. After having analyzed the interests of his listeners, the storyteller needs to give shape to his tale, he needs to make changes and he needs to improvise – thus, this is where the audience holds the strings and the puppeteer is not entirely in control.

In the puppet theaters of Rajasthan, the string puppets made out of wood are popularly displayed in ‘Kathputli’ shows, kath connotes wooden and putli means doll. These dolls have cotton stuffed in their hands and are manipulated by a few strings which are attached to them. With their shows set on a temporary stage, set up against the backdrop of a decorated cloth, these puppets awe both children and adults as they dance and move rhythmically while a dholak (drum) player sings, narrates stories and introduces new characters.

These storytellers mostly have their roots in the nomadic puppeteer community of nat bhats. According to a legend, Brahma the creator, gave existence to Adi, the very first nat puppeteer. Displeased with his performance, he banished him to the earth and thus, the first bhat was born! “While the narrative helps us trace the origins of the community, it also tells us of a higher place unknown to us, from where people could be sent to earth, as punishment, and yet the only place we have ever known, our hell and heaven both; is this very planet. .” The bhats of Rajasthan, travel from one place to another with these wooden dolls and host shows to retell episodes from the Epics, local folklore and from the life of the Rajasthani king, Amar Singh Rathode. Legend has it that when this king governed the land of Nagaur, an impersonator presented himself at his court. This impersonator could alternate between being a man and a woman in the wink of an eye. The puppeteers of Rajasthan skillfully imitate this episode and with a flip of a finger, a male kathputli suddenly becomes female. Again, these storytellers attain the fortune of shifting minds, of playing different characters and of transcending the boundaries defined by strict gender roles. (Read more about kathputli’s here).

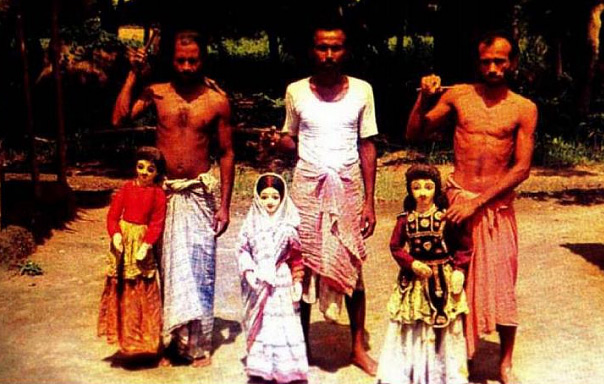

If the puppeteers of Karnataka and Rajasthan narrate stories through the help of string traditions, the puppeteers of West Bengal tell tales with large rod puppets, through a performance known as ‘Daanger Putul Nach’ (the dance of the wooden dolls). Composed of a wooden body and faces painted in ‘pata’ style (clay or a cloth layer on them), as these rod puppets perform on the stage, they resemble the popular musical folk form of Bengali theater, ‘jatra’. Accompanying the puppeteers, there is always a group of talented artists who play the flutes and beat the drums, with a lead singer enthralling the audience with his/her songs.

However, stories narrated through puppetry are not just limited to the Epics, Puranas or ancient folklore. As Dhurjjati Sarma and Ahanthem Homen Singh have pointed out, puppets are not just limited to the sphere of entertainment but throughout time, they have acted as bold critics of the existing socio-political scenarios. So is the case of the hand-puppets ‘Gulabo’ and ‘Sitabo’, the duo which belongs to Uttar Pradesh. In the 1950s, Niranjan Lal Srivastva from Pratapgarh, was a puppeteer who created the story of a man’s imposing mistress, Gulabo and his mundane wife, Sitabo.

As the puppeteer captures the attention by announcing “Gulabo-Sitabo ki gaatha suniye!” (Listen to the story of Gulabo and Sitabo), the audience settles around him to be entertained by the love-hate relationship existing between the wife and the mistress. The story revolves around the constant arguments that take place between the two and the storyteller continuously sings that the duo fights a lot (Dono Khoob Lade!). As the story is narrated, the puppeteer gets the puppets to clap their wooden hands to produce a rhythmic beat while the companions of the storyteller play the dholak (drum). Made entirely out of wood or paper-mache, these well-dressed puppets entertain the audience with their comical behavior while also delivering moralistic messages which concern the society. However, even when the puppeteer wishes to deliver a moralistic message, he needs to disguise it, sweeten the tone, maintain the element of excitement and make an attempt to not offend his audience or even himself…for the puppeteer himself is human and if these inanimate objects point out to the flaws of this society made of us, the puppeteer too is a part of the same society and he too, shares these flaws.

The stories these puppets narrate or the moralistic messages they impart make us aware of all sorts of qualities that people possess and of all kinds of situations that can occur in our lives. The episodes give us the opportunity to explore the ideas of both the protagonist and the antagonist. Perhaps, they give us a chance to understand what we resonate with the most and where our ethics lie on this spectrum of ‘righteousness’. These tales get told and retold, their endings become familiar and the morals they impart become known and yet, we listen to them, time and time again.

In the epic of Ramayana itself, from the beginning of the story, we know what the plot is going to be. In the very first chapter, the readers are told of the heroic qualities of Rama and for them, it’s not a ‘spoiler alert’ to be aware of the fact that Ravana is the anti-hero, his character is not slowly going to shock the readers with his devious acts. Rather, it is an established fact that Rama is the protagonist while Ravana is the antagonist. Thus, what becomes important is not what is going to happen in the story but how is it going to happen. In these puppet shows, mostly, the audience is well aware that the ten-headed demon king is going to be defeated at the hands of mighty Rama and yet, the audience wishes to listen. They stay to see how the tale dramatically unfolds, how the episodes are retold and how these characters incite emotions in those who view them. In some ways, this is also the story of the lives we live. We are all aware of what our end is going to be and yet, we live each day to experience what it has for us. Does this make us an audience of our own puppet show, living each day, to see how our own story unfolds… while being a puppet and a puppeteer both at different levels on this stage, the world is?

Haritima Lal

Iam 14 yrs old and iam very much interested in storytelling..I will be very happy if I will get a chance ..

Laura Simms

I found this a wonderful article that offered so much insight into why puppets are helpful today, when the actuality of their less obvious functions are understood by narrators, and narrator puppeteers. the insight into the uniting of divine and material .. and the flexibility of mind participating in the realm of the puppets that is engendered is so helpful. Thank you. I am a storyteller. And, have been asked to talk about the role of the narrator with puppets.