Syahi Begar

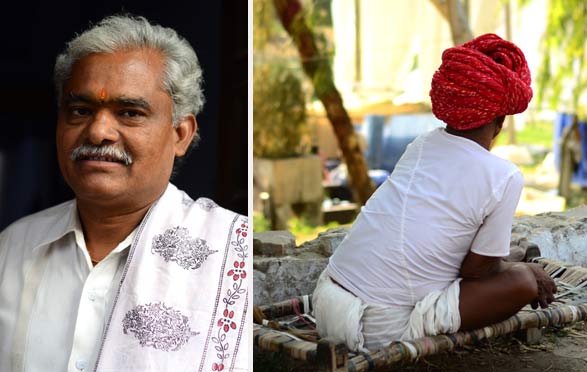

There is something excruciatingly beautiful about a little town in the heart of Rajasthan, specked with colour all the time. With the sun’s heat breathing down on them strongly, bobbed in bright colorful pagdis, the printers walk through the sleepy village located on the edge of a broad riverbank. Sometimes, they have big bundles of freshly printed cloths on their heads, walking through narrow knit streets, where the walls are splashed with colour and the smell of dyes drift through the air. It feels like a water colour painting when the heat causes mirages, with printers walking past in colour-splattered lungis and vests.

From sophisticated printing and dyeing techniques for the royal attire to floral depictions across the local and temple textiles; Sanganer block printing dates back to the social upheavals of mid-17th century that may have forced Gujarati printers to flee to this city in the Dhundhar region of Rajputana, now known as Rajasthan.

Oral tradition suggests that the chhipa families of Jaipur began to shift their work to locations where space and running water were freely available, yet still within easy reaches of the capital city Jaipur. The Kachchwaha Rajput prince, Sangaji, founded Sanganer in the early 16th century and the little dwelling was thriving by the 17th century partially due to its strategic location on major trade routes. The riverbanks of Sanganer presented the ideal location with the added benefit of specialist dyers and cloth bleachers residing in the town. These artisans formed a large, supportive community with block printing at the core of their culture.

The ‘Syahi Begar’ black and red designs on gossamer white cloth adorned the Safa turbans or Angochha shawls of men of the local community. Buti sprigged floral motifs stamped upon softly coloured or white backgrounds graced Jaipur court society. Many chhipas in Sanganer remember the regular production of printed designs for local women. Some patterns mimicked the Bandhani (tie-dyed) head cloths particular to local Mali and Mina women. The bright yellow Mali chunnari or veil cloth is distinctively patterned with a single large red circular motif in the center of the rectangular cloth. On the other hand, the Mina Chaddar, a heavy cotton shawl, is covered with small flower-shaped arrangements of simple red dots on a dark-black background.

Dupattas and shawls bearing auspicious red designs on a white or yellow background adorned the pious attendees at Hindu temples. Home furnishings incorporate a wealth of folk imagery. Regimented borders of flowers, vines, animals and human figures flank the geometric jaal patterns in the center. Ranks of small soldiers accompanied by decorated cows, elephants or horses compete with vignettes depicting popular folk tales.

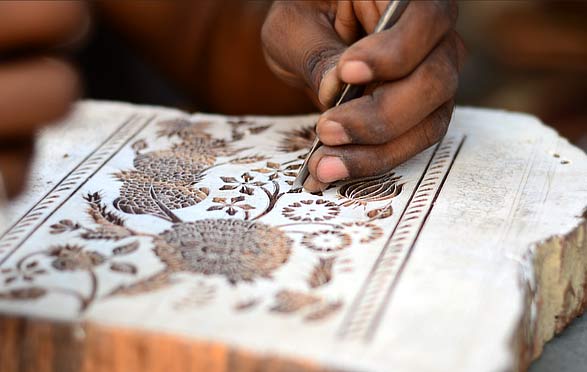

A critical component of block printing is block carving and it is an art form in itself. Two kinds of blocks-wood and metal are made in unique ways and have unique purposes. The traditional printing process began with a rigorous scouring and bleaching procedure called Teluni, to emulsify the oils on the cotton threads.

The cloth was treated with Harda, which functions as a pre-mordant link between the fibers and the various other ingredients. It left a yellowish tinge to the fabric, hence known as ‘pila-karna‘. The craftsman then printed the black area of the design using the Syahi (ink) pinting paste prepared using scrap iron, horseshoes and Gur (jaggery) in an earthenware vessel. After the black outline was made, the craftsman made the Begar, a mordant used for red. Alum was mixed with sticky tree gum paste and a pinch of Geru red ochre to bring out colour in the otherwise transparent paste. The begar paste was then applied using a ‘Datta’ block to fill in the ‘Rekh’ (the outlining block) and the fabric was dried for a week.

The fabric had to be thoroughly washed in order to remove the tree gum. The next step known as Ghan ki Rangai involves use of a copper vessel ‘Tamda’ on a Bhatti. Red dye matter along with Shakur ka phool or dhaura ka phool was added with drop of castor or sesame oil. The printer washed the dyed fabric in the running river water and allowed to dry in the scorching sun with sprinkling of water time to time. This resulted in a bright white background and clear richly coloured butis and butahs.

Over the past three decades, block printing in Sanganer has increased dramatically because of an expansion in the textile market all over the world. There have been a lot of changes with the introduction of chemical dyes in the 1980’s, which slowly led to a vast number of colours, with a boom in the number of possible designs and products, all of which has now given a new identity to Sanganeri printing altogether.

Buy Sanganer Block Print online ~ Shop.gaatha.com