Winds of Change ~ Indian hand Fan (Pankha)

A merchant from the East India Company rushes into his quarters, unable to bear the sweltering heat of India. It had been a few years since he had been stationed here, and there was still so much he was unfamiliar with. While he had slowly adapted to spicy food and alien language, the hot summers of India continued to bother him. Electricity was a novelty and the usual method of cooling down was either to sit under the shade of a tree or to use the Indian hand held fans, pankha. The merchant marveled at the small yet ingenious device that had kept him company on long summer days. With the emergence of electric fans, handheld pankhas have become showpieces in museums with few communities in India handcrafting these beautiful pieces and even fewer using them regularly.

Controversy around the origin of the hand held fan still prevails. Some historians state that it originated in China while others state the place of origin as Japan. Literary sources of both these regions associate the fan with ancient mythical and historical characters. Pictorial records showing some of the earliest fans date from around 3000 BC and there is evidence that the Babylonions, Greeks, Etruscans and Romans all used fans as cooling and ceremonial devices. Two elaborate fans were even found in King Tut’s tomb!

In India, literary mentions of pankhas date back to the Mahabharat and Ramayan. The great poet Valmiki wrote about a fan he once crafted for Lord Ram. The fan shone like a crescent moon in a dim night and it was decked with jewels of vibrant colours. Its handle was sturdy and magnificent looking too.

The word punkha or pankha originates from the word, ‘pankh’ which means feather of a bird. Pankha is used to refer to all fans whereas the word pankhi denotes a small plumed fan used in ancient India. Evidence of the existence and usage of pankhi in India can be found in Buddhist wall paintings at Ajanta. This wall painting dates back to the 2nd century CE. In this wall painting, one can see that a pankhawala is fanning a noble family. Other representations of the punkha can be found on embroidery work, sculptures and carvings. A napkin found during excavations in Chamba carried a drawing of Hindu god Ganesha seated under a palm tree. A king and queen are kneeling beside the tree and using a flag-fan to fan the lord.

In ancient times, pankhas were used in temples to fan deities. They were also used in royal courts to fan kings. Pankhas varied in size from a tiny two inch one to large fans requiring a person’s full arm strength to move them. The Mughals, in fact, employed assistants known as pankha wallas to stand behind them and operate hand fans. Since then, pankha has gained a reputable position of being a royal asset.

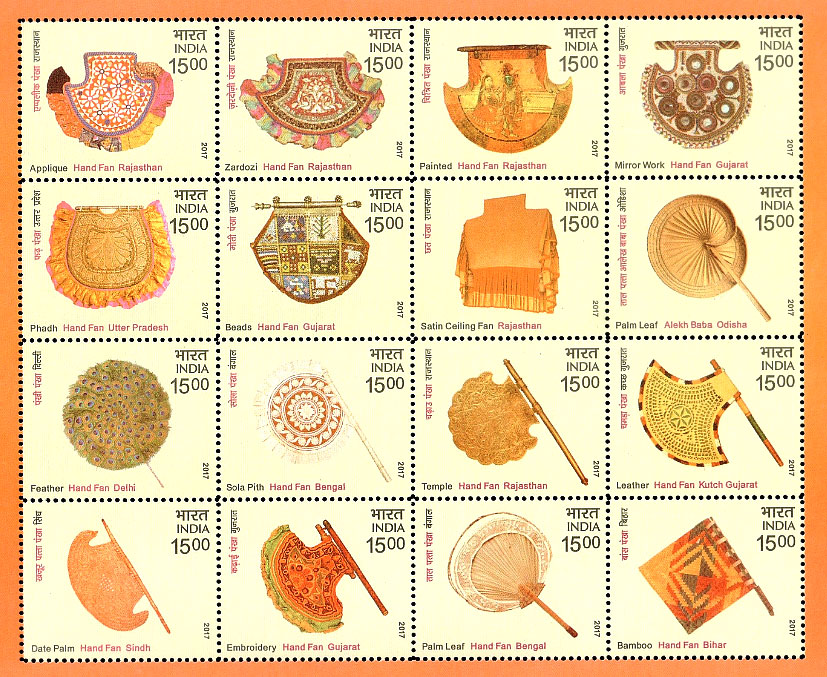

The East India Company helped establish trade routes from India to the rest of Europe, and pankhas became one of the most significant distributed cultural items. They were an exotic and stylish symbol of wealth and class. Although there was substantial commonality in its use across India, different villages and towns developed varieties of traditional pankhas. Each place developed pankhas with a distinct material or diversity of intricate designs that set them apart from each other. Bamboo, cane, palm leaf, silk, brass, leather, and silver pankhas with decorative beads and stones were used depending on geographies, cultures, religious rituals, social protocols, and class structures.

In modern times, the demand for hand-operated fans has decreased. They have been replaced by electrical fans and air conditioners and their use has been restricted to decorative purposes. Pankhas have become traditional craft items in some parts of rural India. The structure of each fan resembles the core of the culture of the region that crafts the pankha. For instance, the applique hand fan of Rajasthan is an antique pankha made of pieces of fabric in different shapes and patterns sewn to another cloth with the use of ornamental needlework. Quite similar to this type of pankha is the Satin Ceiling fan from the same region. Usually used in royal households, especially in medieval India with the help of a pankhawala pulling the device, this pankha is a hand-pulled ceiling fan adorned with silk and satin frills. Furthermore, the Zardozi hand fan of Rajasthan differs in its use of glittering ornate and encrusted gold thread work. In Rajasthan, temple hand fans are popular too. These are made by engraving brass and have a long handle. The painted hand fan, a cardboard pankha with various images, is usually offered to gods, particularly Krishna.

The adjoining state of Gujarat has its own indigenous take on pankhas. The Mirror Work hand fans are elegant pure cotton-based fans embellished with mirror work. The Beads hand fan is covered with colourful beads and has a silver handle. Gujarat is the centre for bead craft in India and these dainty decorations commonly used as wall decorations. Kutch, Gujarat is recognized for its hand-stitched leather hand fans decorated with thread and wool at its seams. Gujarat’s industrious home-based women workers have worked tirelessly in the handicraft of pankha-making to produce embroidered hand fans with traditional mirror work and cross-stitch embroidery in different shapes and sizes.

West Bengal is recognized for its Sola Pith and Palm Leaf hand fans. Artisans in Bengal make delicate pankhas from the beautiful milky-white sponge wood of the Sola tree popularly used for Devi worship. The Palm Leaf hand fans are locally referred to as Tal Patar Pankha. They are easy to carry and are perpetually kept as an article of possession in Bengali households.

Other states in India have their variations of fans too. The Phadh hand fan of Uttar Pradesh is adorned with pure gold, silver zari, silk, and satin frills, the large palm leaf fan of Odisha, Delhi’s feather hand fan composed of peacock feathers and Bihar’s colorful and sturdy bamboo hand fans are all recognized across India due to its antiquity and rarity.

Many tribes in India have adopted this handicraft to make their own versions of the handheld fan. Materials such as grass and metal are embedded into the fans using bamboo sticks and grass. Even cane and palm leaves are used, with silk and brass being reserved for antique pieces of these hand fans and peacock feathers for more aesthetically pleasing adorned hand fans. The use of geometrical patterns and the white ink and red background combinations help the tribes create multiple beautifully designed Pankhas.

With time and the advent of technology and innovative creations, the beautiful culture of pankhas is slowly losing its presence among Indians. With the disappearance of the relevancy of this craft in India, the tradition deeply rooted and tied to India’s craft culture is starting to wither away. Once made for personal use, this handicraft has transformed into a commercial business and now provides some form of livelihood to India’s tribes and rural folk. The tourists, in particular, are incredibly fond of antique items such as the pankha, their slow demand resulting in artisans embroidering and decorating the hand fans in cut mirrors and threads that make them look royal and decorative. The slight increase in popularity and demand is significantly factored by the different versions of the pankha being crafted, some versions even including prints of epics such as Ramayana and others with miniaturized animals catering to a large audience of people who admire the craft of pankha. While the aesthetics of the pankha might appeal to newer consumers, it is imperative to realise that the pankha’s shape and size is quite functional. These days, in case of electricity cuts, people use books or newspapers to fan them. But, since a book is heavy and a newspaper lacks a solid handle, they can only be used for a short period of time. On the other hand, some pankhas have two handles and can rotate 360 degrees to provide air in every direction. Other pankhas that only have one handle can rotate minimally and direct air towards one particular space.

Pankha plays a rather significant role in India’s culture and like Biren Bhuta said, “The loss of culture is the greatest loss any society can suffer.” The artist, Jatin Das affirms that “There is poetry and romance in Pankha. The electric fan moves in a monotonous way, but a hand fan can be used in multiple ways. It is a tool to cajole, seduce, care and love!” One of the first steps to preserve the essence of the craft is by celebrating pankhas, and appreciating the culture, stories, and artistry that this handicraft invokes. It also allows contemporary Pankha makers to demonstrate their craft and regain its popularity and relativity while also helping provide them a commercial platform to create a sustainable livelihood. Initiatives such as pankha making workshops within and out of these exhibitions allow the spread of the beauty and importance of the craft in India’s culture.

ExpoBazaar

Indian handicrafts have always been renowned for their exquisite beauty and rich cultural heritage. The visionary perspective on the future of this industry offers a refreshing outlook. With advancements in technology and a growing focus on sustainability, the possibilities are endless. This commentary opens our eyes to the potential of blending traditional craftsmanship with innovation, creating a thriving ecosystem where artisans can showcase their skills on a global platform. It ignites hope for a future where Indian handicrafts continue to captivate the world and contribute to the preservation of our cultural legacy.

vishal singh

Your blog is a breath of fresh air in a sea of information. Thank you for sharing such insightful and thought-provoking content!

bharat

Fascinating, Indian hand fans are now a part of history, yet they evoke memories of beautiful summer days at your grandmother’s place