Biographies in stone

“My body is but wax and wick for flame. When the candle burns out, the light shines elsewhere.”

Normandi Ellis, Awakening Osiris: The Egyptian Book of the Dead

The Egyptians weren’t the only people to propose that death is but an extension of life. By ensuring that the soul of the king is supported by all material comfort, even after the body has succumbed to the scars of mortality, the men and women only sowed more seeds of faith in life after death. The belief was that the spirit of the late king would protect their civilization from the horrors of nature. Today, in some interior villages of Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Chhattisgarh, a similar analogy can be seen, as the wax of life melts over a moment and instantly gets casted as a stone ‘Gaatha’.

65 year old Shiv Pithadanalal is not an ordinary man. He is transformed into a priest every single time he sits down to make a sculpture. Through his fingers flows a prayer that reveals a familiar image out of fragments of stone. This image of the departed soul might become the only remaining physical embodiment of the cherished one. By ritualistically establishing this link between the two worlds of death and life through his art, Shivji escalates from an ordinary artisan to a monk scripting biographies in stone.

Amongst the other tribes of Madhya Pradesh, the Bhils and the Gonds have been immortalizing their ancestors through stone/wooden Gaathas since centuries. These tribal folk do not worship any particular god or religious imagery, but their own ancestors. Gaatha is a form of sculpture carved in wood or stone after the sudden death of a member in the family. In the occasion of such a misfortune, all the members of the family and extended kith and kin from the neighboring villages arrive to pay homage through rituals amidst devotional prayer recitals.

These rituals require the Gaatha of the person to become the cynosure of reverence, as all present make charitable donations in the form of clothes and other things to the artisan and honor him as the priest of the ceremony being observed. This admiration for the artisan is strengthened by the belief that within the sculpture dwells the soul of the deceased who would solemnly protect the family in the same way as God.

The locals believe that the Gaatha made as a tribute to the departed, should be sculpted before any other auspicious occasion in the family. Previously made by the family members themselves, these embodiments of the protector spirit were placed within the premises of the area inhabited by the community. Unlike a tombstone, it is not laid in the presence of a dead body.

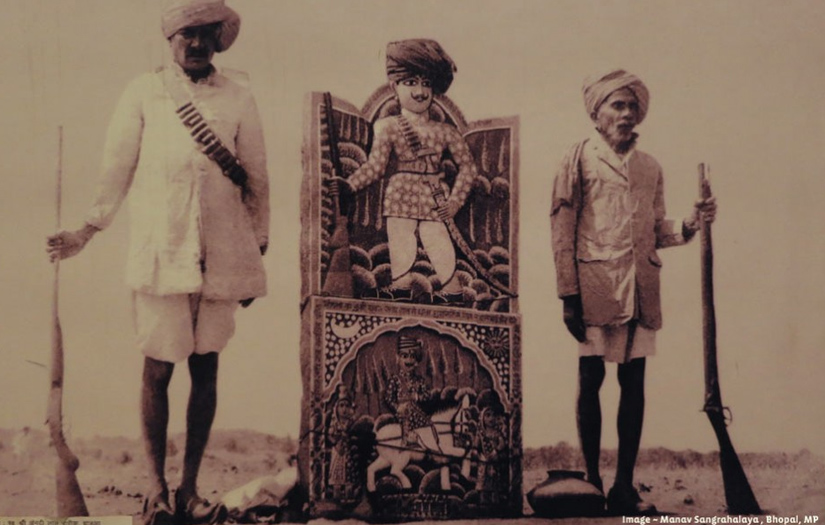

Gaatha Stone – Jhabua, Alirajpur District

The visual details that mark the uniqueness of this art can be quite a feature in terms of iconography. Though the idea is to make the sculpture a thorough look-alike of the mortified, some key attributes of the person are highlighted by exaggerated illustrations… such as popularity in the character of the deceased is depicted by the presence of sun or moon within the frame of his Gaatha, power or wealth is shown by a horse, irrespective of whether he ever rode one or not. Furthermore, to lay more emphasis on the face of the sculpted, it is relatively larger in proportion than the body. Interestingly, the women are featured fairly simple. Without any other iconic depictions surrounding them, they are usually shown as a single figure.

Staphana Stone – Chhindwara, Dindori District

In the bygone era, the priest would sculpt on a word of mouth description provided by family members. Today, the photograph of the person in context fulfils the purpose. Lastly, the name of the individual is also carved on it.

The process of making a Gaatha requires a surface such as sandstone or a wooden plank. The surface is ritualistically prayed every time before sculpting the figure on it. The portrait of the person is first sketched on the base and then carved out on the same lines. A third dimension is further added by giving it a depth of about an inch. Traditionally, ‘geru’ was used to stain the stone or wood in brick red. But as these tribes were exposed to the modern means, the culture of painting these sculptures with commercial grade paints started about a hundred years ago. A singular Gaatha can be crafted within a fortnight.

The cost factor varies from rupees 5,000 to 30,000 depending on the size and the spending power of the relatives. While the Gonds customarily lay their Gaatha under shade, the Bhil prefer positioning them in open spaces. The Gonds infact address the same craft as ‘Sthapna’ (comes from the Sanskrit origin ‘sthapna’ meaning to situate) and use fairly large stones. While Gaathas of Jhabua area use iconic imagery to represent attributes related to the person, those in Chindwada region are much closer to the real. Apart from Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, areas in Gujarat and Rajasthan are also known to practice the custom.

The word Gaatha otherwise means a story. But here, it is the personification of the numerous tales that sculpt in their different ways an individual’s life. It hence becomes difficult to argue whether the artisans make the spirit of a man immortal, or add that touch of a timeless legend to an ordinary inanimate stone. But like they all say, men may come and men may go, but their ‘Gaatha’ stays forever.

~

Read more about craft ~ Gaatha.org