Laathi-charged

Paan, neta, jalebi, uparwaala and lathi…. A popular Sunday times article defines these amongst others, as those torchbearers of Indianness, that should last even if doomsday may swallow every other living identity of our dear country. Amongst these, the lathi is perhaps the most significant witness of changing times.

Traditional Lath Or Lathi

In a time where it is more widely recognized due to the notorious idiosyncrasy of the lathi charge, this wooden staff definitely possessed a more distinguished virtue in the bygone days. Obvious that is from the fact that native Indian proverbs still mention the heroic qualities of the lathi through phrases like “andhe ki laath, jiski laathi uski bhains, saap bhi mar jaaye aur laathi bhi na toote” and others.

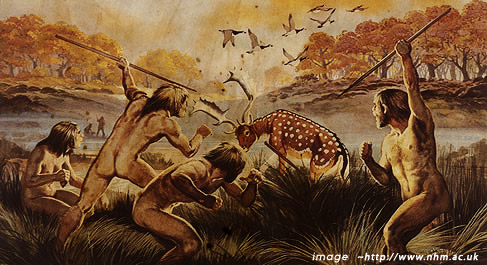

From the Neanderthal man who used the stick for hunting and way finding to today’s young village lads who flaunt their stick as an emblem of their newfound masculinity, the lathi hasn’t really changed much. This 6 feet long multipurpose, lean and mean wooden staff has always been used for acts of defense and comes handy for everyday utility as well. The easy availability of material for the tool and the very idea of a stick in the hand, which equips man with an invisible power and fearlessness, ensure that the popularity of the lathi remains unparalleled and timeless.

The lathi as a weapon is as old as a man’s need to survive harsh uncertainties. The earliest dwellers of the civilization have used the stick to walk and navigate across difficult terrains, to control and protect domestic animals, to defend themselves against thieves and other herdsmen, or carry parcels made of cloth containing food and other necessities, tied around their stick while away from home. From the village head or Sarpanch to the rented villains hired by rich Zamindars to oppress poor farmers, the lathi has been a favorite accessory for all …. a noble companion for the good, bad and the ugly. The tribal people were however the first to innovate in decoration of the everyday lathi, using various burnt patterns and symbols, characteristic to their tribes. Stick-fights which involve lathis have been a popular sport in many parts of East and South India. Even today the lathi is a key prop for various native martial art forms and traditional dances.

The craft of making and adorning the wooden stick evolved in Nawakheda (Ujjain), Shahjahanpur in Madhya Pradesh. Here people have been making the ‘lath’ for centuries now. The art of ornamentation of these wooden sticks is fairly recent though. According to veteran craftsman Shri Rampuri, today approximately 20-25 families pursue this craft to the extent of occupational practice.

It is interesting to observe that these craftsmen do not sell as much from their village, as they do from the animal fairs such as ‘Pushkar mela’, ‘Chaitra mela (Barmer)’ etc. They generally establish a temporary settlement in these fairs and move into these with the rest of their family. Furthermore, all the raw materials required for the craft are acquired from the surrounding villages/town of the fair.

The raw materials required for this craft are Bamboo sticks (ingenious to Uttar Pradesh and Chandrapur in Maharashtra), metal wires and other accessories for ornamentation (usually bought in from Delhi and Jaipur). The rough and naturally curved bamboo sticks are heated and pressure bent in the direction opposing their natural curvature, this way they lose moisture and straighten over their length.

By filing these sticks, their surface undulations and nodes are shaved off. In order to make theses sticks moisture proof and increase their overall strength, groundnut oil is rubbed along the entire surface in the presence of heat. This process also reduces the susceptibility of the treated bamboo to insect infestation. The native craftsmen interestingly lend color to these bamboo sticks by polishing them either with a mixture of burnt ash and groundnut oil (for a homogeneous burnt brown color) or a mixture of groundnut oil and edible yellow color (which imparts a clear and even yellow tone).

Once dry, the sticks are ready for ornamentation. This part of the procedure has children and women folk as active participants. Colored radium strips and metal bands are assembled on the wooden staff in the desired arrangement and board pins are hammered into them in such a way they are only halfway through into the wood.

This tact serves the dual purpose of holding the arrangement in place while giving ample pivoting space for the bunch of 3-4 soft metal wires that create a decorative mesh, meandering along the entire length of the wooden staff and getting locked around the stems of these board pins at regular intervals. To witness the craftsmen engage in the aforementioned procedure is indeed a visual delight because the wooden staff held between their feet, rotates as it would on a lathe machine, and the hands gracefully indulge in timed adornment with the metal wires.

Even though majority of the used raw materials are sharp and rough, it is fascinating to touch and caress the smooth surface of the end product, which discloses the keen labor that goes into giving the wooden staff a flawless finish. The aesthetics of the wooden staff are further enhanced using metal bells and musical trinkets. By addition of loops to ends of these sticks and producing varieties of the shorter brethren of the lathi, the craft has only pleased the masses more than ever. Designs carried out to beautify the wooden sticks have hardly lost any original chutzpah and remain very similar in intent and execution to their original prototypes.

The craftsmen use principles of division of labor and ensure that the major chunk of the work is done in lots as it probably would on a production line. A single visit to their temporary yet robust bamboo stalls would leave one positively amused at the sight of the multitude of certificates displayed from the various fairs that the artisans have participated in.

Call it the most ancient weapon of the world which is used even today as a crowd control device, or call it a mere stick with an inflated ego, there is more to the lathi than what meets the eyes. And in this wooden baton lie thousands of our ancestral tales wrapped like a soul that only grows…but not old.

SANJEEV ARORA

Hi, wud like to purchase the Beautiful laths that u Sell. How do I Order & Select design. Is there any Retail Outlet in Delhi/NCR.

Thanks & Regards

\Sanjeev arora