Gamocha from Assam

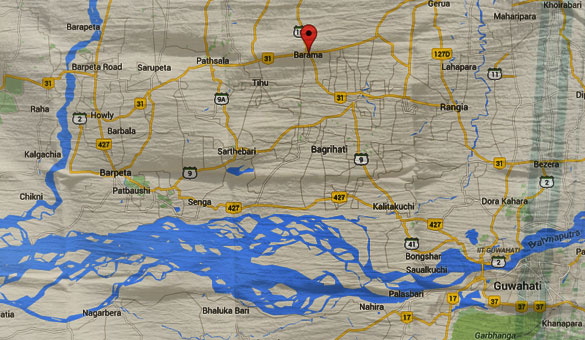

Nestled among wetlands, rice fields, lush greenery and river banks; Barama Block in Baksa District, Assam, lies about 70 kms from the state capital of Guwahati. The relatively new district was carved out from neighbouring Nalbari district in 2003 after the autonomous Bodoland Territorial Council came into being. After decades of violence due to various militant groups, the area is finally experiencing a time of relative peace and quiet.

Handloom weaving has a very large presence in the socio-economic life of Assam since time immemorial. The loom is a ubiquitous possession, used by women in almost every household as a way of life. It is one of the oldest and largest industries in the state. In olden times, the skill to weave was the primary qualification of a young girl for her eligibility for marriage. The tradition of weaving is passed on from one generation to another and is widely seen even today.

Barama Block which is home to a number of different groups including Bodos, Assamese, Rabhas, Bengalis etc witnesses a great diversity in the local culture in terms of eating habits, ritual practices, language and so on. This multi-cultural identity of the area is also reflected in the clothing patterns and the weavers’ output. While the Assamese weavers weave gamochas and mekhela chadors, Bodo weavers weave aronais, dokhnas, and lengas. They also weave other fabrics like handkerchiefs and shawls.

The techniques of weaving have been handed down over generations, allusions to which are available in Assamese scriptures and literature, with very little change. Weaving in the state is known for its pristine simplicity and unequalled charm.

All kinds of materials are used for the fabrics. The most commonly used materials are cotton and acrylic. Weavers also use wool and various variations of silk – including Muga and Eri, which are indigenous to Assam. Early in the morning, the process starts with putting the yarn into circular rolls, bobbin, through two spinning wheels. After this, several of these bobbins of red and white colours and fitted into a contraption called the ‘Xaja’.

After this, the threads are spread out through the Xaja. For the gamocha, 470 threads are necessary with mainly white threads and periodic intervals of red threads. Similarly, other garments have their own count of threads necessary – chador needs 1,000 threads, a mekhela needs 900 threads, a wedding ‘Gamocha’ which is known as a ‘Pinda’ needs 800 threads. After spreading them out, each thread is then individually put through a metallic frame with small openings for the threads, to separate them.

It is important to note here that the weavers will not weave only one Gamocha at a time. Since the process is laborious and time-consuming, they will weave several Gamochas at one time. I was informed that there is enough yarn to weave about 18 Gamochas in a stretch. In fact, the household was weaving these to give out during the celebration of Bohag Bihu, a celebration to mark the beginning of the Assamese New Year on the 13th of April every year.

After this, the eldest woman member starts to weave the Gamochas. The constant movement of the hands and feet leads to a rhythmic sound which is soothing and musical. However, this is not an easy task. The weaver has to use both her hands and legs to complete this task – the hand is used to move the bobbin which controls the horizontal thread with the help of a handle; the leg is for pedalling the fabric forward.

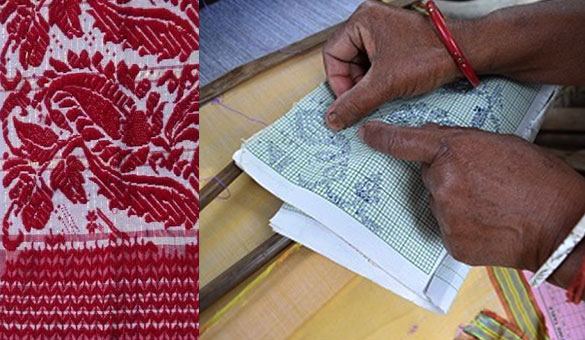

While this Gamocha has a relatively simple checked pattern with no flowers or designs, the weavers also make garments with elaborate designs and flowers. Even these intricate motifs are woven by hand, as most of them don’t possess a ‘Zakat’ or flower machine. For Zakart it is important to get the design drawn on a graph paper. Each block on the graph paper represents one or a set of two threads. Depending on the design, the weaver must weave thread for the motif either above or below the other thread. This is an extremely delicate procedure.

Very few of these weavers however sell their clothes in the market. The few who do sell their products in the market usually don’t own any land and do it out of compulsion, rather than choice.

The lack of commercial activity related to handloom can be attributed to several reasons including oversupply in the local area, seasonal demand and no market linkages with other markets in nearby towns and cities. For commercial activities, several models are practised. Some of the forms are:

– Weavers weave clothes mainly for their own household and will take orders only during festivals such as Durga Puja, Bihu, and Kali Puja

– ‘Aidha’- means half-half. Customers will buy inputs and provide it to the weaver. The weaver will then weave clothes – keeping 50% of it for her and giving the rest to the customer.

– Weavers sell their fabrics in the local bazaars every week/fortnight

All the women members of the extended family came out for the exercise. About four women contributed to it at different times during the day, for different activities. As the sun began to set, they decided to call it a day. Looking at the whole process made me realise that it brings the whole family together. All the women members pitch in to help, and help from neighbors is not unexpected, either.

~

Text & Images by

Sujan Bandyopadhyay