Amidst Rays of Hope and Sunlight – Bagru Block Print

Under the reign of Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II, in 1730, a horde of families made its way to the newly built Jaipur. It had only been three years since the city named after its King was established, making it his new capital. The sun was sinking amidst the clouds, painting the sky a brilliant periwinkle, its warmth on their tanned skins reflecting the warmth they felt as they listened to their children laugh and play. The children were sitting on ox-carts, creaking under the strain of them and their belongings. This cacophony of a community bonding over a voyage became quieter as the dark of the night enveloped them in its loving embrace.

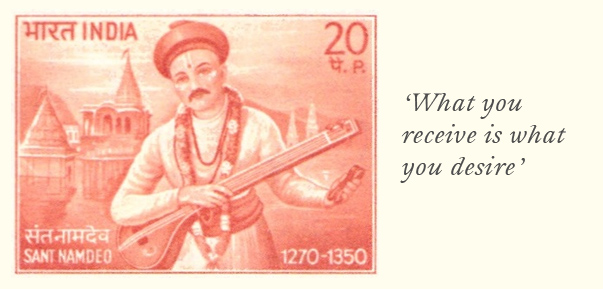

Their home of many years had given them plenty to live for, but as their sources dried up, they knew it was time for them to move on. They had lived a hard life in the past days but as they walked then, their faces were set with determination and their eyes shone with the prospect of a better future. They shared the celestial poetry of Saint Namdev, their ancestor who lived in an age long gone by, amongst themselves. This is my message, Says Namdev

This verse rang true when they came across a piece of land near Jaipur, soil-rich with the waters from river Sanjaria. They rejoiced and settled down with newfound hopes in the place that would come to be known as Bagru. They molded themselves to the place perfectly, or perhaps it molded itself to them. Nonetheless, they stayed and when stability made itself known, they began working. They donned garbs of their own making, different patterns indicating the sartorial roles their community had. Their work gained repute when the royal family became their patron. On the rare occasions that the king made an appearance in public, the Chippas, for that’s what they were called, swelled with pride when they saw him donning a pagdi, bold patterns marking it as a creation of their own.

Theirs is the blood that runs through the veins of the man who now sits down for a conversation with people traveling from far to know about their art, several generations later. His community is now of international fame, known for a craft called Bagru Block Printing. Yet, it’s hard to find words that can encompass the beauty of this craft. The afternoon is quiet, courtesy of the children being at school rather than their homes. The heat is keeping the people inside but the smell of Sohan halwa being stirred in the kadhais in shops lures people out of the comfort of their homes slowly.

Holi is around the corner and the very air seems to be quivering with excitement. The man’s ears are craving to listen to the melodious evenings filled with folk songs and the sounds of sarangis and jhalars. These festivities begin a fortnight before Holi and are accompanied by graceful movements of the Chari dancers. It will be a delightful event, he assures the guests.

For now, he has to be content with his work, and wait patiently. The air of the Chippa Mohalla—the area of the town that belongs to the printers where he is sitting now—seems permanently ingrained with the smell of drying fabrics. The courtyard is filled with a plethora of these rippling fabrics, washing the sun-lit area in a rainbow of black, cream, brown, beige, and red.

The man breathes in the air and looks around at his fellow printers as they work through the various stages of the craft. He realises he has found the words he was looking for, so he begins speaking in a coarse Rajasthani.

The demands of the market being at an all-time high, with fifty years of dryness of river Sanjaria, was a huge hurdle in the lives of the printers. But the Chippas are strong and despite losing the cool waters of the river, they have found ways to stay their ground. It is the ability of his people to deal with what life throws at them that tinges the man’s voice as he shows off an assortment of different tools—chisels, wooden blocks, colour trays, printing tables and more.

The hands of the printers never stop working, starting with ridding the fabric of starch and other impurities with the help of soap water. When it is sufficiently dry, it is primed in a mixture of cool water and harda, a natural mordant. It is then hung to dry under the scorching sun, sporadic bursts of air making it flutter softly.

While it does so, a myriad of different colours is prepared. These printers are few of the handfuls who still use their traditional methods of using vegetable dyes. In the whirlwind speed of modern times, the Chippas somehow remain unhurried, letting their craft shine.

The reds for the dyes are made from fitkari(alum), madder root, and babul gond(a natural gum paste). The blacks are made with syahi(fermented rust from burnt horseshoe, jaggery, and water). The vibrant blues, perhaps, take the longest. They are made from natural indigo in V-shaped wells called Naand, leaving the Indigo with casatoria seeds to ferment for months. As the man moves around his printing workshop, he can spot coriander sprigs, pomegranate rinds, and rose petals. He knows these would yield vibrant colours as well.

The man’s hands become animated as he elucidates the importance of the one thing that made these prints into the magnificent art they are: the wooden blocks. The importance is, perhaps, emphasized by the fact that carving wood is an art form in itself. These are carved before the process with the fabric begins.

“My friend here,” he motions towards one of his fellow Chhipa printers, “decides how many blocks to use by the number of colors and shapes that are going to grace the fabric. Then another friend carves out the wooden blocks. The wood is chosen carefully. We use seasoned Sagwan, Rohida, or Sheesham wood.”

The motifs in the blocks that he shows are unlike each other. Some sport whorls and flowers while the others feature circles and other geometric patterns. “We need three kinds of blocks for a print. The first one here is called a Gadh and is used for the background. Then for the outlining, we use Rekh. To fill in the colours, a Datta is used. I carve a handle on the other side of the blocks for a proper grip and drill holes in the blocks to let out the excess colour. We need the print to be perfect, you know. Lastly, I leave the block to soak in oil for a fortnight so that it softens the grains in the wood.”

The man himself is wearing a kurta, patterned in a monochrome black, that hadn’t needed the Rekhand the Datta while printing. The credit for this goes to the modern prints his community had readily embraced. They required a clever play of negative spaces that he had mastered. Even so, the traditional prints required all three blocks.

These blocks lie in the lower rack of the patiya (a tray trolley) until it is time for the printing. Once the printer realises the fabric is dry, he pins it over a large printing table covered in canvas and jute. The patiya lies beside the table, holding colours on the upper rack. This colour is poured over a saaj (the tray) and a wire mesh is laid on top. A scrap of felt is fixed over it, absorbing the colour nicely. Lastly, a cloth of mul mul (fine cotton) is kept on top. This process is done so that the colour stays on the pattern on the wooden blocks and doesn’t drip on the fabric. It is how a stamp ink functions, but on a much bigger scale.

The printer picks up the Gadh from a section in the patiya, dips it in the saaj, and presses it firmly onto the fabric. Then he pounds his fist against the center of the handle and a flower blooms on the pale fabric. This process continues in uniformity until the desired background is accomplished across the fabric. He then outlines the print with the help of Rekh, pressing and pounding the wooden block. Then comes the colouring, with the help of Datta. The rhythm and harmony of this process, which leads to a perfect print, could be the inspiration for a musician to create something equally perfect.

The colour red doesn’t show up as red when printed. So, the fabric gets boiled in water with alizarin in a tambadi (copper vessel), which brings out the red. The fabrics are given a final, quick wash and left to dry. Finally, they are ready to be in a new home.

When the tour around the workshop is over, the man, after a quick chai break with his friends begins his routine walk towards home. As he passes the bazaar, he notices his people in brightly coloured attires nodding amiably at a pair of tourists. He nods at them as he buys mangodi for his children from a nearby stall. His wife usually makes them at home but he had a sudden craving and knew his children loved it too. When he reaches home, he sighs in relief and stretches his muscles, which are sore after a day well spent. When his children rush towards him with toothy grins, he wonders if life could get any better.

~

Gaatha

India’s longest-running craft documentation project since 2009.

We have researched 250+ living craft traditions through field visits,

artisan interviews, and cultural study across India.

→ Explore our Bagru research archive at gaatha.org

→ Buy authentic Bagru textile at shop.gaatha.com