I weave your name on the loom of my mind

जब मैं था तब हरि नहीं, अब हरि हैं मैं नाहिं।

प्रेम गली अति सॉंकरी, तामें दो न समाहिं।।

These lines were written by Kabir, one of the greatest poets to grace Indian mainland. The word ‘Kabir’ is derived from the name of one of the Gods in Islam. People often refer to this mystic poet as Das, Sufi-Saint or Bhakt.

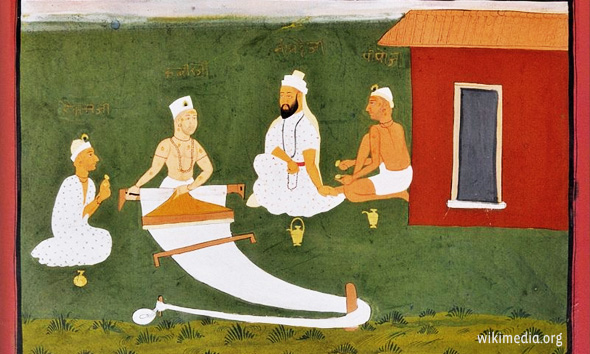

Born in fifteenth century in Benaras, when the city was facing a cultural concoction with the Bhakti movement, the early life of Kabir played a crucial role in the formation of his spiritual ideologies and the tendency to observe with reason. Kabir remained a disciple of Ramananda for several years. Frequently accompanying his guru to discussions on theology and philosophy held with Muslim intellectuals and Brahmins shaped his thoughts and introduced him to Hindu and Sufi philosophy.

Kabir was not a sanyasi, neither did he leave the family life nor did he spent days meditating in forests. He lived in a weaver’s neighborhood and obtained his livelihood by trading the cloth woven by his family. Writing was something which came to him while he worked on his loom, meditating with his mind fixed on alternating warps and wefts. Here is one of his numerous songs, which were inspired by the craft of weaving:

I weave your name on the loom of my mind,

To make my garment when you come to me.

My loom has ten thousand threads

To make my garment when you come to me.

The sun and moon watch while I weave your name;

The sun and moon hear while I count your name.

These are the wages I get by day and night

To deposit in the lotus bank of my heart.I weave your name on the loom of my mind

To clean and soften ten thousand threads

And to comb the twists and knots of my thoughts.

No more shall I weave a garment of pain.

For you have come to me, drawn by my weaving,

Ceaselessly weaving your name on the loom of my mind.

He was an eloquent observer with an opinion that was unaligned and perched on fair-mindedness. His poems often interpret the trivialities of life. One day Kabir went to the Bazaar to sell the loom’s cloth. The weather was chilly with a heavy breeze. When he came across a scantily dressed Sadhu, the poet gave away all of the loom’s produce. On his return his dear ones asked him, why he had done so, he answered by saying that you should give as long as you live. If your boat is filled with water or your home with wealth, it is wise enough to empty it using both hands.

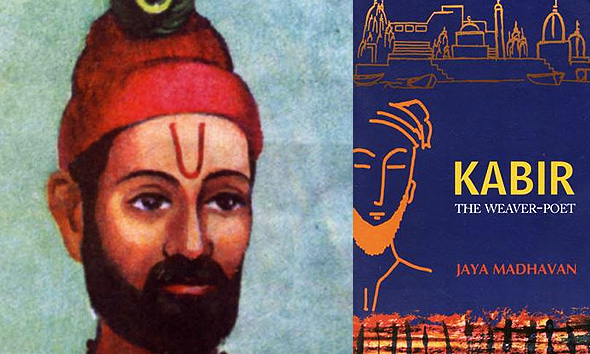

An excerpt from Jaya Madhavan’s ‘Kabir the Weaver- Poet‘ narrates how Kabir inculcated his thoughts into weaving:

“Everyone’s focus now turned to the fabric Kabir had spent a week weaving for the Pundit in addition to the mat he had ordered. Wanting to put touches of design in other colours into the weave, he set about preparing the dyes. Into four different vats, Kabir tossed peels, shells, flowers, leaves, twigs and barks — things nature discarded and no longer needed. Turmeric went into the first vat to make yellow dye. The second one had iron shavings brewing in vinegar to make black. Kabir set aside lac and iron shavings for red. Blue from indigo he already had from the previous week’s brewing. Kabir now used that indigo to mix with pomegranate rind to extract a darker shade of green. Into the fourth vat went sandalwood and rose attar solutions. The dyed threads would soak in the fragrant solution before being dried and loaded onto the loom. That way the entire fabric would smell of sandalwood and roses.

Once mounted, the threads fell in neat dots each time Kabir worked the pedal and pulled at the string of the jacquard box hanging above the Loom. The dots fell — yellow, green, blue, red and black — populating the pink and green muslin, making it look like a group of people gathered on a field one bright morning. The dots came alive in Kabir’s eye as the people of Banaras. In them he recognised the Potter and the Tanner, the blacksmith, washermen, weavers, goldsmiths, acrobats . . . even the Mullah and the Pundit.

Through all this ran the river of silver dots – Ganga, quietly nourishing its people without prejudice, without differentiating between rich and poor, high and low, Brahmin and untouchable, Hindu and Muslim. Flecks of gold shone like benevolent spirits hovering above to guide and protect the people. When Kabir stepped back to see his handwork, it was not just he who gasped, but also the Spindles, the Charkha, the Takli and the rest of the weaving gang. The design was breathtaking, fit for none less than the gods! Kabir saw the wisdom of his heart, the rhythm of his poetry and the depth of his feelings reflected in every hue, dot and fleck stamped on the spellbinding mulmul khus.

“This is nothing,” whispered Kabir. “I have run mere cotton threads for the warp and weft. But how did God, the Master Weaver, make this finely woven fabric we call skin that we wear all our lives? What is the warp? What is the weft? What fine thread does he use?” wondered Kabir and broke into a song.

Jhini jhini bini chadariya,

Kaahe ka tana, kaahe ki bharani,

Kaun taar se bini chadariya?

Kabir sang, deeply immersed in love for the Master Weaver who ran bright coloured threads across the sky to weave mornings and later dyed them in orange and black to make evenings and nights. From the magical skin we wear to the fabric of the sky, the Master Weaver weaves them all — finely, expertly. The rest listened in silent awe.”

Kabir received a wide reception for his thoughts, the whole world still chants his prose and quotes him while upholding a reason. The weaver community across India regards him as their deity and Kabir’s temples can be seen across India. However, it is something which was against his philosophy. In one of his works he had written: “As the sesame seed has oil enclosed in it and as the spark is imbibed in the stone, even God resides within everyone and everything.”

In reverence for the great weaver poet, Government of India distributes a prestigious Sant Kabir Award for the master craftsmen across India, who have contributed significantly to the promotion, development and preservation of weaving tradition and welfare of the weaving community and over 55 years of age.

Kabir’s wisdom was not restricted to a certain group or ideology, Kabir was of anyone who listened to him. His legacy is carried forward by Kabir Panth. Across india people sing his songs and vocalize his writings which are valid even in modern times. The Kabir project, an initiative by Shabnam Virmani explores how his poetry intersects with ideas of cultural identity, secularism, nationalism, religion, death, impermanence, folk and oral knowledge systems.

http://youtu.be/Z-cTnh6npn8

Credits ~

SONGS OF KABIR ~ by Rabindranath Tagore

Translated by Rabindranath Tagore

KABIR , A WEAVER POET~ by Jaya Madhavan

a book by Tulika Publishers,

http://www.kabirproject.org

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kabir

http://www.easwaran.org