From Soil to Soul: Indigo in India

When you hear the word Indigo, what do you picture? Maybe a deep blue fabric, or a certain shade in your crayon box. But have you ever paused to think about the word itself? Indigo—where does it come from? And more importantly, is that what we’ve always called it?

In many Indian homes, the word you’ll hear instead is Neel. You might recall it being added to a bucket of white clothes or used in temple clothes dyed a soft, faded blue. Neel feels familiar. It belongs. Indigo, on the other hand, feels like something introduced to us, rather than something we’ve grown up with.

That feeling isn’t wrong.

India has known this colour for thousands of years, long before it was bottled, branded, and shipped across seas under the name “Indigo.” Our ancestors cultivated the plant, dyed cloth with its extract, and traded it with distant lands. Blue, in Indian culture, has never been just a colour. It holds deep symbolic meaning. Think of Krishna and Shiva, both depicted in shades of blue. The sky, the oceans, the cosmos, all vast, powerful, and untameable, are blue. In mythology, blue is associated with the infinite, the divine, the protective. So when Indigo was used on cloth, it wasn’t just for aesthetics. It carried an aura of sacredness and mystery. The colour spoke not only to the eye, but to the spirit. Yet, over time, this legacy was interrupted. What once belonged to us was repackaged, renamed, and even redefined.

Let’s look at Neel again, not as a borrowed colour, but as a native presence. We’ll travel back to its roots in Indian soil, its presence in our daily lives, and the ways colonialism turned it into something else. This is not just a story about a dye. It’s a story about memory, loss, resilience, and reclamation. Because before it was Indigo, it was always ours.

Before factories and foreign demand turned it into a global commodity, Indigo was deeply rooted in Indian life. The plant that gives this colour, Indigofera tinctoria, is native to our land. It grew alongside crops, between riverbanks, in monsoon-soaked soil, and under the care of farmers who knew exactly when to sow and when to harvest.

Evidence of Indigo’s presence in India goes back centuries. Archaeologists have found traces of blue dye in the ancient sites of the Indus Valley Civilization. That means as early as 2500 BCE, our ancestors were not only growing the plant but knew how to turn its leaves into a vibrant, lasting dye. This wasn’t a small achievement. It needed deep knowledge of fermentation, temperature, and timing, all passed down without books or manuals.

In Tamil literature, especially the Sangam texts, Indigo finds mention in descriptions of trade, clothing, and even landscapes. Buddhist Jataka tales, dating back to the 4th century BCE, also speak of blue-dyed clothes, worn by monks, gifted by kings, or sold in bustling markets. These weren’t just coloured fabrics. They were markers of place, identity, and memory.

Across the subcontinent, Indigo took on different shades of meaning. In Bengal, it coloured the borders of dhotis worn in everyday life. In Rajasthan, it was part of ceremonial dress. In the South, it turned up in Kalamkari textiles, temple cloths, and even as symbolic offerings. It was present in mourning rituals, and in joyous festivals too. The colour blue wasn’t just worn, it was lived with. Unlike today, where colours are often separated by geography or market demand, Indigo once had a much wider presence. It was woven into daily life across the subcontinent, a common thread connecting distant places and diverse crafts.

What makes this relationship even more unique is how Indigo touched so many layers of life. It wasn’t limited to artisans or elite patrons. Farmers grew it. Women helped process it. Dyers transformed it. Traders carried it. In each region, a slightly different word existed for it, Neel, Neeli, Neelam, but the connection remained the same: close, continuous, and very much Indian.

This wasn’t just a dye we produced. It was a colour we knew, used, and understood in our own ways, long before the world learned to call it Indigo.

At the heart of Indigo lies a plant, small, unassuming, with soft green leaves and pinkish flowers, that quietly holds centuries of history. Indigofera tinctoria isn’t dramatic in appearance. But in its leaves, it carries the secret to a colour that the world once could not get enough of. What makes Indigo even more fascinating is the transformation it undergoes. The plant doesn’t look blue at all — its leaves are green. The dye vat, when prepared, also appears greenish-yellow. It is only after the fabric is dipped in, then brought out and exposed to air, that the iconic blue appears. How did people figure this out, centuries ago, without chemical instruments or modern labs? The process seems almost magical. But generations of observation, experimentation, and intimate attention to nature allowed them to understand this pattern. What we now take for granted was once a mystery decoded by patient eyes and practiced hands.

What made this plant special wasn’t just the dye it produced, but how closely it was tied to the land and the people who nurtured it. Indigofera grew well in warm climates with plenty of rain and slightly alkaline soil, something India had in abundance. It was often grown alongside or between other crops, sometimes rotated with cotton or pulses to keep the soil fertile. It didn’t just take from the earth; it gave back too. As a legume, it fixed nitrogen in the soil, enriching it for future harvests.

Indian farmers knew how to care for it. They understood its needs, timed the sowing with care, and harvested the leaves at the right moment, often just before flowering, when the dye content was highest. But growing the plant was just one part of the process. Extracting the dye required precision, patience, and deep local knowledge. Farmers who grew Indigo knew its rhythms deeply. They could tell which part of the field would yield the best leaves. They knew that the first harvest wasn’t always the strongest — it was the second or even third crop that brought out the best pigment. Timing mattered, as did soil, temperature, and even the way leaves were plucked. This wasn’t casual agriculture. It was knowledge built over years, often passed down through generations like a precious family recipe. Often, what we see in the final Indigo-dyed cloth doesn’t reflect the amount of labour that went into it. There’s the farmer who grew the plant, the person who fermented the leaves, the one who ground the cakes, the dyer who prepared the vat, the spinner who turned fibre into thread, and the weaver who brought it all together. And before any of that, someone had to process the leaves, prepare the cake, and ship it across regions. The chain is long, invisible, and deeply human. Each layer adds its own quiet fingerprint to the blue.

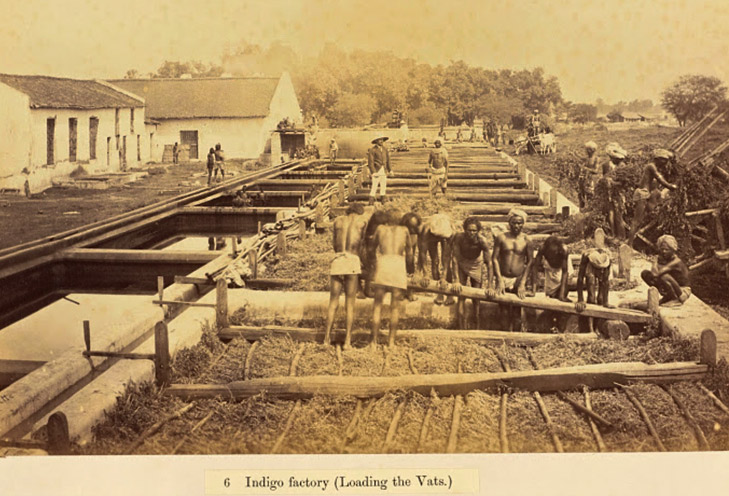

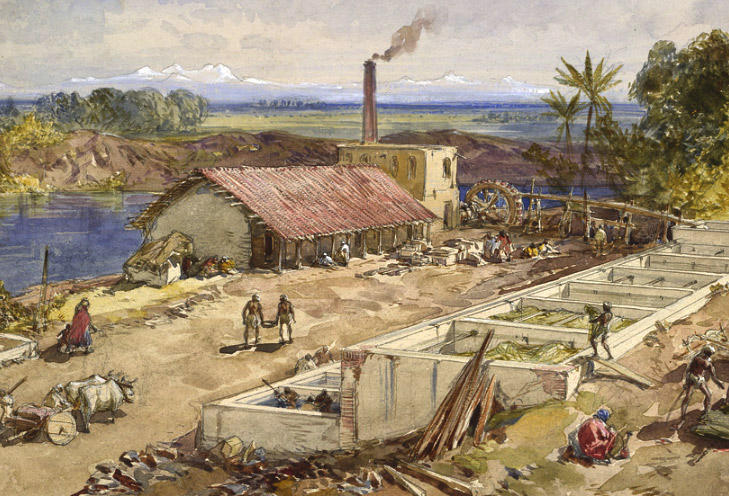

The process involved fermentation. Leaves were soaked in large vats of water and allowed to sit. As they broke down, they released a substance called indican. This liquid was then stirred, beaten with sticks, and exposed to air, slowly turning blue as it oxidised. No chemicals, no machines. Just hands, air, and time.

Many of these vats were built generations ago and passed down like heirlooms. The work was often done near wells, rivers, or tanks, always close to water, because water was key to Indigo’s transformation. In many communities, women played an essential role in this process. They helped crush the leaves, stirred the dye baths, and knew how to test if the colour was ready. Their knowledge was quiet, but precise.

Behind every indigo-dyed cloth was a network of people, skilled hands, patient minds, and deep-rooted knowledge systems. Indigo was never the work of one individual. It was always a community effort, woven into the fabric of daily life.

In India, the dyeing of cloth has always been a tradition. Indigo work involved farmers, fermenters, dyers, washers, spinners, and weavers. In some regions, the same family might have done it all. In others, each step passed through the hands of a different group, each one a specialist in their own right.

Dyers, or Rangrez, were some of the most central figures. In towns like Sanganer, Kutch, Machilipatnam, and beyond, families of dyers worked with natural colours for generations. They knew the behaviour of Indigo intimately, how it reacted to heat, when it deepened in tone, when it faded, and when it stayed true. They didn’t follow written recipes. Instead, they learned by watching elders, by dipping and redipping cloth, by reading the colour through sight and smell.

Some groups, like the Chhipas of Rajasthan, were known for their block printing skills and used Indigo alongside other natural dyes to create vibrant patterns. In the South, artisans working in Kalamkari used Indigo to outline divine stories on temple cloths. In Bihar and Bengal, where the climate suited Indigo cultivation, entire villages were involved in its farming and dyeing.

But Indigo wasn’t only in the hands of professionals. In many homes, especially in rural India, women used Indigo casually, to add a touch of blue to white saris or household linens. The Neel that was added to buckets of water wasn’t always store-bought; in some homes, it came from their own backyard or community dye pit. It was common, but never ordinary.

Each region developed its own techniques. Some places used Indigo to resist dyeing, creating patterns by covering parts of the cloth with wax or mud. Others used it in combination with iron or jaggery to shift the shades. The knowledge wasn’t uniform, but it was everywhere, living, breathing, adapting.

And with each generation, the craft was passed down like a story, not always in words, but in gestures, routines, and muscle memory. This made Indigo more than just a material. It became a symbol of collective identity, where colour wasn’t just applied, it was understood.

But that quiet began to fade when the world, especially Europe, began to take notice of the deep, lasting blue that came from Indian soil. What followed was not just admiration, it was extraction.

By the 17th and 18th centuries, European traders and colonisers had begun to see Indigo not as a craft, but as a cash crop. Part of the reason Indigo fascinated European traders was because it was unlike anything they had known. In colder climates, wool was the dominant textile — and wool rarely took on vibrant colour. Black, grey, and brown were the norm. Indigo, with its striking, luminous blue, felt exotic, luxurious, and even magical. It stood out in European markets, and its appeal quickly turned into demand, which in turn became pressure on Indian producers. The demand for blue-dyed textiles was growing across Europe, and India, with its long-standing expertise and fertile land, seemed like the perfect supplier. But instead of collaborating with Indian artisans and farmers, colonial powers sought control.

In Bengal, British planters forced farmers to grow Indigo under exploitative systems like the tinkathia, where farmers were made to grow Indigo on a fixed portion of their land, often against their will and at the cost of food crops. They were paid little, and sometimes not at all. Processing centres, called Neel Kothis, sprang up across the region, run by Europeans and enforced by local muscle. Farmers had no say in the pricing, the crop cycles, or even in how their own land was used.

The dye that once came from community effort and knowledge was now reduced to quotas, contracts, and punishments. What was once a practice rooted in care became a source of suffering.

But the story didn’t end in silence. In 1859, Bengal saw a massive uprising known as the Indigo Revolt. Thousands of farmers refused to grow the crop. They marched, protested, and stood united. The movement was one of the earliest signs of organised rural resistance in colonial India. It forced inquiries, debates in British parliament, and eventually a slow rollback of Indigo farming in some parts.

Even so, the damage was done. Many traditional dyeing centres weakened under the pressure of industrial systems. With the arrival of synthetic dyes from Europe in the late 19th century, natural Indigo faced further decline. Factories could now produce cheaper, quicker versions of the colour, without the plant, without the people, and without the memory.

The result was a shift in perception. What had once been ours, grown in our fields, used in our rituals, known in our languages, became foreign in our own eyes. The word “Indigo” replaced neel, neelam, and neeli. The dye came to be seen as a colonial product, even though its roots ran deep in our soil.

Indigo is also a reminder of something larger. Time and again, India has developed rich systems — in textiles, farming, medicine, and art — only to have them disrupted, rebranded, or extracted by outsiders. Yet, years later, these same practices are being revisited, celebrated, and sought after by the very powers that once dismissed them. Indigo is not just a dye; it is a reflection of knowledge systems that were always right, even when they were ignored. It tells us how much we knew, how much we lost, and how much we still carry — quietly woven into the blues of our past and present.