CARTing ~ The Bullock Cart Makers of India

At the crack of dusk Hiraman cracks up Sultan. “Enroute Mandi”, he shouts in their code language. By-passing their rustic hamlet, Sultan slows down near the lake, so Hiraman can catch a longer glimpse of Laila drenched in froth. Sultan is his best friend and his sole source of livelihood too, and it is hard for him to separate from it, which results in him taking utmost care of his vehicle. Hiraman’s bullock cart helps him carry goods to the market and transport him from one place to another. And also, a lot of the ordeals he faces in his daily routine, are therefore ingrained in Hiraman’s deep attachment to his bullock.

For instance, carrying black market goods one day… almost landed him in trouble with the local police, who could in no way miss noticing this tall, hefty, beauty of a best marching alongside motored transport on the road. Transporting inconvenient materials such as long bamboo sticks on top of that, causing a bit of chaos all around. On another occasion, giving a ride to a random nautanki dance group, that made noisy music wherever they went, had almost costed him his life… riding on sleepless days and nights one after the other, he almost rode them off the road into a bottomless trench, when the reigns were pulled out of his hands by the dance girl, and the cart brought back on the track. And our poor Hiraman, so awestruck by her beauty was left heartbroken, when he helplessly attached a few strings here and there with the maiden of the group. These instances are a reflection of a bullock cart drivers’ relationship with what he carries along with him in his cart in general…. And in this story, Hiraman’s.

Bollywood has gloriously highlighted this relationship for years, from Raj Kapoor’s 1966 starrer ‘Teesari Kasam’, to further down in the timeline, in Amitabh Bachchan’s 2020 starrer ‘Jhund’… Bullock carts have not only been an integral part of the Indian rural life but also the lives of urban dwellers, in the form of these films.

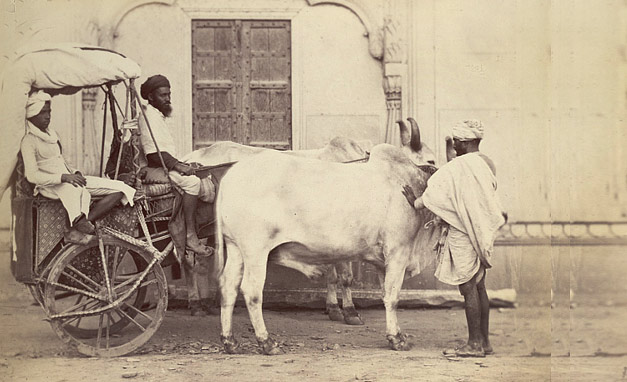

Dating its origins back to the Indus Valley civilization, bullock cart was an indigenous innovation in the alluvial plains of India. Along with agriculture and hunting, trading of goods was one of the most extensive uses for bullock carts for the people of Indus Valley civilization. It helped them expand their culture and provided better access to trade with other civilizations.

From transportation of goods such as terracotta pots, beads, gold and silver, colored gemstones, metals, flints (for making stone tools), seashells and pearls, the emergence of these bullock carts also drastically changed the volume of goods that could be transported; stone, mud-brick, water, clay, wood, heavier materials could be carried for short distances across the plains; an essential factor that serves people significantly in rural India till date.

Interestingly, the history of artifacts is a highly revealing factor for the civilizations and their utilisation of certain items. Toys, in particular, are an integral part of traditional cultures across the globe. Terracotta bullock carts with movable parts found at excavation sites of most Indus settlements provide a glimpse into the significance bullock carts held to the Harappans. The craft of making bullock carts expanded into the art of making terracotta and wooden replicas, possibly for the play of their younger population. A charming copper model of a cart found at Harrapa, in particular, holds a close resemblance to the present-day ‘Ekka’. Ekka is a one-animal carriage with canopies commonly used as cabs or private-hire vehicles in 19th century India and can still be found in northern India. A reference to these toy carts is made in a medieval Sanskrit play called Mricchakatika (The Little Clay Cart), written by Indian playwrighter, Shudraka around 2nd century BC. The play follows a noble but impoverished young Brahmin, Cārudatta, who falls in love with a wealthy courtesan, Vasantasenā, and makes her his mistress. In an episode, Vasantasenā and Cārudatta’s young son is distressed because he enjoys playing with his friend’s toy cart made of solid gold, which makes him resent his own clay cart. Taking pity on the young boy, Vasantasenā fills his little clay cart with her jewelry, heaping his humble toy with a mound of gold. This play is one of the many depictions of bullock cart toys in India’s cultural history.

The cultural representation of bullock cart has led us to visualise it with a bullock carrying a cart on its shoulders with two wheels attached. But owing to diverse topography, different breeds of bullock and the purpose they serve, the design of the carts have to be customised uniquely. For example, if an area receives high rainfall and the soil is marshy, the wheels of the bullock cart have a larger radius. If the terrain is uneven then the cart is without an axel. Carts for the races are designed comparatively lighter and have short wheels. Thus the community involved in bullock cart making takes inputs and engineers continuously in order to make a cart that fits its purpose, terrain and the bullock it is going to get attached to…

Artisans who are involved in making carts are predominantly from the Vishwakarma community, which traditionally comprises of two sub groups- Sutar (carpenter) and Lohars (Blacksmiths). As the popularity of Bullock cart and the wealth it brought increased, the creativity of the craftsman to increase its aesthetic value also grew. They sought help from Chitrakars (painters), Kasars (bronze smiths) and shipakars (sculptors) who eventually became a part of the cart making community.

Initially prevalent as a means of livelihood, the making of bullock carts with good quality wood became a prominent artisanal tradition in many parts of India. With simple tools like Saw, Hammer, Axe (Kulhari), Peeler (Randha), Chisel (Chorsi), Scale (Guniya), the Vishwakarma community applied their knowledge of carpentry to create something indigenous.

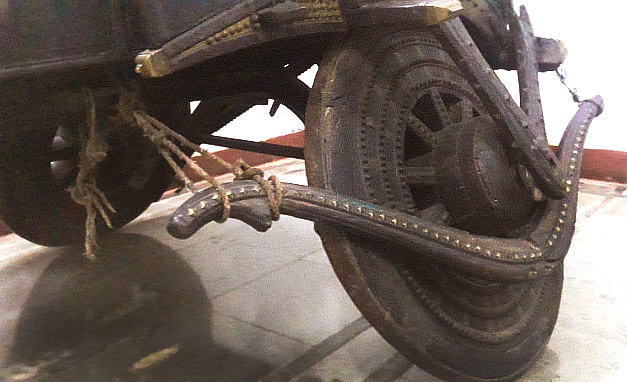

The wheel of the cart is made in parts. A single part consists of a spike which are then connected together with an interlocking joinery system at the center of the wheel. The iron strip that protects the wooden wheels of the cart has to be heated to the right temperature to be wound around the wheel. A quick and delicate pouring of cold water on this heated iron strip tightens the metal strip onto the outer surface of the wheel. The axle, made by a strong wooden beam is rested in a hub without any bearing and requires careful and intricate knowledge of joinery and loading capacity for its implementation.

The frame of the cart is usually trapezoidal in shape. The shape became more common due to its longer life and lesser maintenance. The frame, which defines the cart’s size, is connected to the axle using a simple rope or with interlocking joinery with wooden nails to make it more stable. The yoke, the energy harnessing part of the bullock cart, is fabricated such that it causes no harm to the hump of the bullock & supports the mainframe, subsequently carrying the cart’s entire load.

The beauty of a bullock cart goes beyond its basic framework, when the user exercises his freedom to further enhance the aesthetics and functionality according to his taste. For example, the width & the height of the cart is customised according to the products it is supposed to carry. Carts to be used in muddy areas have a spike on the wheel that constantly removes the mud stuck to the wheels. If the purpose of the bullock cart is transportation of the people, the canopies to protect from the overarching sun are crafted with indigenous crafts. Even for the bullocks; neck belts and halters are specially handmade to add a vibrant, hyperlocal touch.

Making of bullock carts with good quality jungle wood as prominent artisanal tradition relies on locally procured raw material. For instance, the craft of making and repairing bullock carts in Karnataka’s Ganjam area, near Srirangapattana, has been carried over for generations now and their carts are renowned for their durability and excellent craftsmanship.

The Bullock Cart Makers of India: A Craft on the Verge of Extinction

When the Industrial revolution struck India, to keep up with modernisation, even the craft of Bullock carts started incorporating modifications to match the efficiency of machines. Iron wheels replaced wooden wheels of the traditional carts, with different parts such as the hub, spoke, etc. also getting metallic gradually.

A lack of demand in traditional means of transport after the automotive industry in India took off led to shrinking of the craft to a bare minimum. It has been kept alive there after, not by its agricultural use, but rather by its recreational use and display of it as a novelty, but the cultural significance of bullock carts still continues to prevail in people’s lives. In many villages of Sindh, Punjab, Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra & Madhya Pradesh people still enjoy bullock cart rides and Bullock cart race is a popular sport. Moving musical groups and street theatres also find their accessible mode of transportation in bullock carts.

Restored carts of unique origins make for exquisite displays in museums and architectural spaces today…. Though we seldom see a complete cart, restored and displayed in its full glory. The restoration process is picking up pace as a reminder of the beautiful origins of our automotive industry as we make our footing stronger on the soil of Mars with vehicles carrying the best we have of technology yet maintaining in appearance the very basics that remind us of what we deem primitive in our hyper plasticised decorative societies on Earth today.

~

Gaatha

India’s longest-running craft documentation project since 2009.

We have researched 250+ living craft traditions through field visits,

artisan interviews, and cultural study across India.

→ Explore our research archive at gaatha.org

→ Buy authentic Indian crafts at shop.gaatha.com