Crackled Colours

A few kilometers from Ujjain, on the banks of river Kshipra, is the small town of Bhairavgarh. Known for the temple of Kaal Bhairav, the fearful manifestation of Shiva, also for tantriks who perform occult rituals in cremation grounds and the fables of king Vikramaditya and vampire spirit Betaal, this town also holds within itself, something not so dark and mystifying.

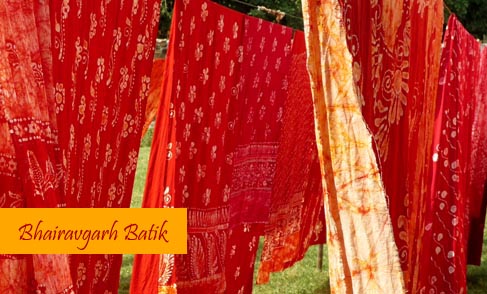

Batik Bhairavgarh Ujjain

Glowing yellows and intense hues of reds brighten the streets of this town, with fluttering lengths of cloth printed with patterns of melted wax.

Batik, the ancient technique of wax resist dyeing, is believed to have been practiced in Africa, China, Japan and India for more than 2000 years. Bhairavgarh became the hub of Batik printing in Madhya Pradesh, when craftsmen from Gujarat and Rajasthan came here during the reign of the Mughals, around 400 years ago.

Originally batik printed cloth was used by the tribals of surrounding areas for their draped garments, but today, all sorts of dress materials, sarees and home furnishings are made in with this technique and sold across the country.

In the workshops of Bhairavgarh, craftsmen are busy doing what seem to be swift doodles on fabric, but what emerge are beautiful motifs of flowers and leaves, creepers spiraling and twisting in perfect symmetry. Vats of hot wax slowly steaming on gas burners stand alongside large sand covered tables, on which the animation of wax lines would take place. Sand avoids melted wax from touching the table and sticking the fabric along with it. With a stylus made by tying coconut husk on a metal rod, craftsmen draw out perfect wax patterns on fabric, with no guidelines, no rough sketches. Spontaneous images that come to their mind are immediately transferred on to fabric like improvised harmonies.

Some also use wooden blocks for creating slightly more restraint designs, although the melted wax gives even the crisp blocks a slight quirky flavour, with its slightly out of the lines colouring.

Once the wax dries, the fabric is dipped in dye. Colour stains the exposed area and when the wax is melted in hot water, white motifs can be seen on a coloured field. This process of application of wax and then dyeing is repeated for as many colours as required, starting from the lightest, and going to the darkest.

Large areas of the cloth are sometimes covered entirely with wax and once dry, the fabric is crushed, to break the cooled wax. After dyeing, this gives the typical cracked effect characteristic of Batik.

The base fabric is sourced from Rajasthan or Tamil Nadu, but craftsmen sometimes use local Chanderi and Maheshwari fabric as the base for printing, combining two handicrafts of the state for a charming fusion.

Natural dyes are used only rarely, usually for Kalamkari designs, but other than that, the use of vivid chemical dyes is prevalent. Industrial candle wax has replaced natural wax, due to which the proportion of wax that can be reused has decreased. These are resultants of a demand for cheaper materials and faster processes.

In a state where refined, delicate weaves like Chanderi and Maheshwari dominate, along with the fine block prints of Bagh, the batik of Bhairavgarh strives to carve its niche, and how beautifully it does!

Read in detail about Ujjain Batic ~ Gaatha,org

Vimal

Very useful knowledge about batik print.

Thanks for sharing it.