From Rags to Riches (Jhabua Dolls)

A little girl sits on her bed, eyes twinkling with mirth. Her parents have returned from their trip and she knows they are going to surprise her with a present. Her father comes into her room with his hands behind his back and mother follows in tow. They sit down and he shows her the gift. She claps and clutches the doll to her chest. It is different from the conventional, plastic dolls her friends from school play with. The dolls in her collection are softer and their dresses remind her of her grandmother’s loving hands. She asks them, like always, about the people who make them and they, unlike always, decide to indulge her.

They tell her about a town in Madhya Pradesh called Jhabua. It is a town where people of art reside. Its people, despite the harsh sun turning their skins bronze after working the fields, know how to celebrate. The town listens to the tinkling laughter of the youth as they chase each other in the festival the Bhils—the native tribe—are well known for. The Bhagoria Haat, as it is called, is also traditionally a place where people choose their partners. Under the deafening noise, children feast their eyes with beautiful wares and their mouths with jalebis and pethas. One of these beautiful wares are the cloth dolls that are so coveted by the little girl.

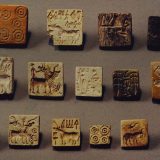

Dolls have been a source of comfort and joy for people as far as living memory goes. Countless little girls in India, from about 5000 years ago, have loved and played with dolls. It may be because of the sustainability of cloth as a material and the ease with which it moulds itself as the maker desires. In Jhabua, the craft of doll making was revived in the 60s. When a bride is leaving for the groom’s house in their culture, they are gifted with a doll to accompany them. When children are born, they are gifted with these dolls too.

The uniqueness of Jhabua cloth dolls is evident through the traditional garb that they wear. These dolls, which can even be as tall as a little girl itself are an embodiment of a person belonging to the Bhil tribe. The bodies are made out of fabric scraps in shades of brown that perfectly capture the sun tanned skin of the people. The locals call this style of doll making “Adivasi Gudiya Hastshilp”.

“The women of the tribe sit in a many-hued sea of sarees. Just as you would sit spooled up in your grandmother’s wardrobe full of colourful sarees.” Their’s are the skilled hands that begin the process of making these dolls… with sketching out the shapes of the parts of their bodies and dresses on chosen fabric pieces.

These colourful fabrics, so vital to this craft are collected from households around Jhabua. There are a myriad of prints and dyeing techniques in these fabrics that add to the charm of these dolls. The fact that they are fabrics handed down after they’ve already spent a life as someone’s garments or decor makes them a bit more friendly to mother nature and a bit more special to the buyers of these up-cycled dolls.

Two layers of those drawn out shapes get cut out and with a whirring sound of the sewing machine meddling with the ongoing gossip, they get stitched together. These stitched pieces are then turned inside outer and stuffed with cotton to give them life. To make the doll whole, as they should be, all the scattered parts are stitched together, keeping the seam beneath the two feet open. The technique used for stitching these is called the ‘Pakkatanka’—a double knot.

The faces of the dolls are formed with clay and are carved out with extreme care. They are then fired to make sure the clay gets firm and are then covered with cloth. Nimble hands then paint the expressions on their faces carefully, a task that requires great expertise.

Then comes the most important part which is the clothing. The female dolls are adorned with bead necklaces (galsan mala) or silver necklaces (chandi ki haansli) and bangles (kadas). They are made to wear the colourful Bhagoria bridal Ghagra and Choli. Household items like bamboo baskets and earthenware are given as accessories.

The male dolls, on the contrary, are made to wear Dhoti and Kurta. They are equipped with the traditional occupational tools—the teer kamthi (bow and arrows) used for hunting, the spears for harvesting, the scales for weighing. Embellishments like zari, sequins and ribbons sourced from nearby towns are used to make the dolls lovelier. The outfits represent the Bhil and Bhilala tribes, their occupations in life and ethnicity.

The final step of this wonderful craft is fixing the dolls onto the wood base. Metal wires are inserted in the legs of the dolls from the opening. These wire ends protruding from the doll’s feet are put through the base and hammered mildly from the back side of the wooden base until they are fixed in place. If it feels like the dolls are missing something, it is fixed with the help of paints. Finally, these dolls are ready to be bought and cherished by little girls and many others as gifts.

Despite the fact that it is a well loved craft, the demand for it has been mellow at times. With many people earning livelihoods through this craft, it is all the more important that this age-old tradition is carried on. The craft must thrive, so that another generation may witness how rags are brought to life again through these dolls.

As the tale comes to an end, the little girl pulls her new doll closer with droopy eyes. She is delighted to know of the place her treasure comes from. Her parents finally tuck her into the bed. Before she falls asleep, two promises are made. The first one is for herself, that she would continue her collection of dolls even after she grew up. The second one is from her parents and is the sweetest promise because it is a promise of a new tale on the next morrow.

For more detail – Visit Research & Archive portal

Rajni

Well written!

vishal singh

I appreciate the incredible depth of knowledge your blog provides. It’s truly exceptional!